How All Creation Glorifies God by Being What It Is

Abstract

This paper explores ontological truth—the intrinsic truth of being itself—as revealed through the natural world. Using the contrast between the mango (a symbol of delight) and the cane toad (a symbol of repulsion), it argues that both are ontologically perfect and glorify God by fulfilling their design. Drawing on Scripture—especially the Psalms—and the works of Augustine, Aquinas, Bonaventure, and modern theologians, it further proposes that the Fibonacci sequence expresses the mathematical language of creation’s order. Through these patterns, we see that all existence, whether pleasing or unpleasant, participates in a continuous act of praise: creation worships God by being what it was created to be.

1. Introduction: The Ontological Nature of Praise

“Let everything that has breath praise the LORD.” — Psalm 150:6

“The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of His hands.” — Psalm 19:1

Humanity often measures beauty by its sensory appeal. Yet Scripture insists that all creation—not only the beautiful—praises God. The Psalms describe creation as a vast choir of being: the heavens, mountains, rivers, and trees all proclaim divine glory through their very existence.

This vision invites us to look beyond surface attraction or repulsion to see ontological truth—truth grounded in being. Whether the object is a sweet mango or a rough-skinned cane toad, each fulfills a purpose in God’s order and thus participates in the praise of creation.

2. The Fibonacci Sequence: The Ontological Signature of Creation

“He has made everything beautiful in its time.” — Ecclesiastes 3:11

“O LORD, how manifold are Your works! In wisdom You have made them all.” — Psalm 104:24

Across nature’s forms—the spiral of a galaxy, the curl of a fern, the seed pattern of a sunflower—the same quiet arithmetic unfolds: the Fibonacci sequence

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34,…

Each new term equals the sum of the previous two. This recursive law gives rise to the golden ratio (φ ≈ 1.618), a proportion appearing in living organisms, shells, flowers, and even human anatomy.

The simplicity of Fibonacci conceals a profound theological truth: growth and harmony emerge not from randomness, but from mathematical obedience. Creation flourishes because it follows a divine pattern written into its being—a truth that is ontological, not metaphorical.

As St. Augustine taught,

“Numbers are the universal language offered by the Deity to the human mind for the confirmation of truth.” (De Musica, VI).

And St. Thomas Aquinas affirmed,

“Order is the first notion of the good in creation.” (Summa Theologica, I, q.47, a.1.)

Thus, Fibonacci’s law is a visible grammar of being: a cosmic hymn rendered in number. Every spiral, petal, and curve becomes a verse in creation’s mathematical Psalm.

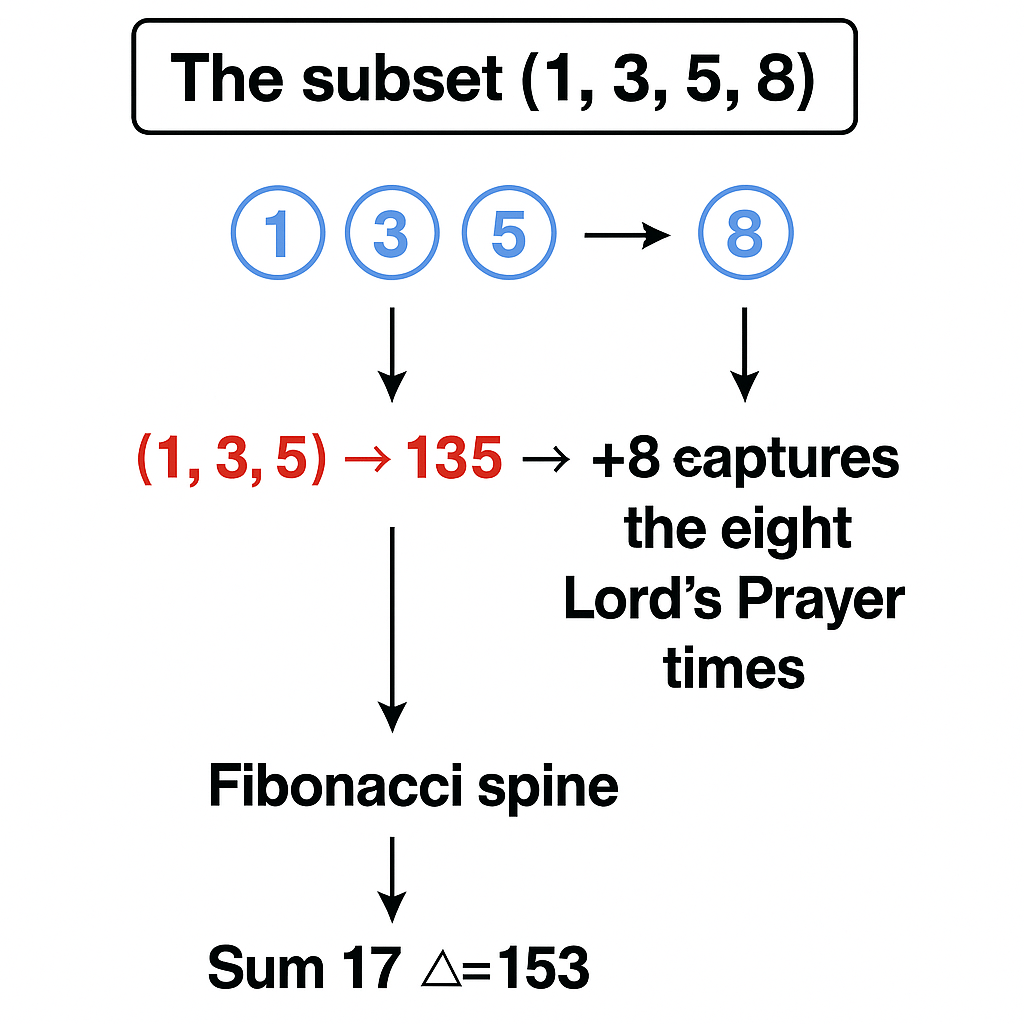

2.1 The Minimal Subset {1, 3, 5, 8}: The Lord’s Pattern in Nature

Within the sequence, the subset {1, 3, 5, 8} forms a “Fibonacci spine.” Its sum equals 17, and the 17th triangular number is 153, the Gospel number of ingathering (John 21:11).

This pattern links natural growth to spiritual order. The digits (1-3-5-8) later correspond to the eight daily times of the Lord’s Prayer (10:35, 10:53, 13:35, 13:53, 15:15, 15:51, 17:13, 17:31), expressing the same logic: creation praises God through ordered recurrence, while humanity joins that order through prayer.

The Fibonacci principle therefore expresses ontological praise—the way creation worships by existing according to divine proportion.

3. Defining Ontological Truth

Ontology (from Greek on, being, and logos, reason) examines what it means to exist.

- Aquinas taught: “Omne ens est verum”—everything that exists is true, because all being flows from the God who is Truth Itself (ST I, q.16, a.3).

- Augustine wrote: “God is the measure of all being; every creature is true insofar as it reflects divine order.”

- Bonaventure called the world “a book written by the finger of God” (Itinerarium Mentis in Deum, I.14).

Ontological truth, therefore, is not abstract doctrine but the living reality that a thing is true to its design. A mango, a toad, a mountain, or a star glorifies God simply by existing as it was intended to be.

“The LORD is righteous in all His ways and holy in all His works.” — Psalm 145:17

4. The Mango: Ontological Delight

“Taste and see that the LORD is good.” — Psalm 34:8

“He makes grass grow for the cattle, and plants for people to cultivate—bringing forth food from the earth.” — Psalm 104:14–15

The mango’s fragrance, sweetness, and golden color seem perfectly tailored to human delight. Its flavor tempts the tongue, its ripeness signals through color, its seed ensures propagation. This harmony is not coincidence but ontological coherence—a sign of creation’s underlying order.

In the mango we taste the goodness of being itself. It glorifies God not by words, but by perfection of form and function. It nourishes body and soul; it is what it was created to be.

Aquinas captures this well:

“Each thing tends to its own perfection, and in this tendency the order of creation is manifest.” (ST I, q.47, a.1.)

The mango’s existence is therefore doxological—an edible hymn to divine goodness.

5. The Cane Toad: Ontological Repulsion

“All creatures look to you to give them their food at the proper time.” — Psalm 104:27

“Even the wilderness and its creatures honor me.” — Isaiah 43:20

The cane toad (Rhinella marina), warty and toxic, elicits revulsion rather than delight. Yet its design is equally perfect. Its leathery skin prevents dehydration; its parotoid glands secrete toxin to deter predators; its dull coloring provides camouflage.

What humans call “ugly” is in truth functional excellence. The toad survives, controls pests, and maintains ecological balance—fulfilling the purpose for which it was created.

Augustine reminds us:

“All things are beautiful in their place, though we see not the beauty of each part by itself.” (Confessions, VII.13)

The toad glorifies God through obedience to its design, not through human approval. Even its repulsiveness teaches humility: divine wisdom exceeds our aesthetic boundaries.

6. The Logic of Both: Ontological Praise

“Praise Him, sun and moon; praise Him, all you shining stars! Praise Him, you highest heavens!” — Psalm 148:3–4

“Fire and hail, snow and mist, stormy wind fulfilling His word.” — Psalm 148:8

The Psalms name opposites—light and storm, beauty and chaos—as equal agents of praise. Likewise, the mango and the cane toad form two poles of creation’s harmony:

| The Mango | The Cane Toad |

|---|---|

| Symbol of beauty and delight | Symbol of utility and endurance |

| Reveals God’s generosity | Reveals God’s wisdom and justice |

| Pleases the senses | Challenges the senses |

| Teaches gratitude | Teaches humility |

Both are ontologically perfect, each revealing a different facet of divine character. The mango’s sweetness and the toad’s toxicity are not contradictions—they are complementary notes in the same cosmic song.

To exist according to one’s design is to worship.

7. Fibonacci Ontology and the Eightfold Rhythm of Prayer

The subset {1,3,5,8}—a Fibonacci “spine”—sums to 17, whose triangular number is 153, the Gospel’s number of ingathering (John 21:11).

- Nature’s ontology: 1 + 3 + 5 + 8 = 17 → T₁₇ = 153

- Church’s doxology: 153 × 8 = 1224 → value of “the net” (τὸ δίκτυον) in John 21

The eight Lord’s Prayer times (10:35, 10:53, 13:35, 13:53, 15:15, 15:51, 17:13, 17:31) extend this pattern into lived devotion.

Creation’s Fibonacci order becomes humanity’s daily rhythm of sanctification.

Thus, Fibonacci mathematics discloses ontological truth in structure, while the Lord’s Prayer transforms that truth into spiritual rhythm. The two together reveal that mathematical law and liturgical life are one continuum of praise.

8. Theological Synthesis: Creation as Continuous Worship

“All your works praise you, LORD; your faithful people extol you.” — Psalm 145:10

“You preserve both man and beast, O LORD.” — Psalm 36:6

Ontological truth transforms our view of nature. The world is not random; it is a choir of being where every entity sings by fulfilling its form. The mango praises by sweetness; the cane toad by resilience; the Fibonacci spiral by order; and humanity by recognition.

When humans pray, “Your will be done on earth as it is in heaven,” we align our choices with the same order that nature already obeys. We move from observing praise to participating in it.

9. Conclusion: The Psalm of Being

“Let everything that has breath praise the LORD.” — Psalm 150:6

In the final vision, no creature is ugly, no pattern arbitrary. The mango and the cane toad, Fibonacci and Psalm alike, form a single revelation: creation’s ontological truth is its praise.

Whether delightful or disturbing, fragrant or foul, all things proclaim:

To be what God designed you to be is to glorify Him.

This truth dissolves the divide between beauty and necessity, between mathematics and theology. It turns every act of being into a verse in the eternal Psalm of the Logos.

References

- Scripture: Psalms 19, 34, 36, 104, 145, 148, 150; Isaiah 43; Matthew 6; John 21.

- Augustine. Confessions; De Musica VI; Enchiridion.

- Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologica, I q.16, q.47, q.65.

- Bonaventure. Itinerarium Mentis in Deum.

- Balthasar, Hans Urs von. The Glory of the Lord.

- Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre. The Phenomenon of Man.

- Pitre, Brant. The Lord’s Prayer and the New Exodus.

- Vanualailai, Jito, et al. The Lord’s Prayer: A Mathematician’s Creed.