Abstract

This paper presents a theological and mathematical reading of Psalm 7 using the Verse Identifier method (Book + Chapter + Verse) and the Canon of Numeric Invariants (divisors, sum-of-divisors, divisor mean, and related measures). Two principal findings emerge. First, the “moral recoil” unit of Psalm 7:14–16—where evil is conceived, set as a trap, and returns upon the perpetrator—yields an identifier total of 123 whose sum-of-divisors is 168. Strikingly, 168 is also the identifier total of Luke 11:2–4, Luke’s core presentation of the Lord’s Prayer, culminating in deliverance from evil. Second, the full-psalm identifier total 595 possesses a divisor mean of 108, a number treated in our apologetic framework as a symbolic marker of counterfeit completeness when devotion is detached from Christ. These results invite a coherent theological interpretation: Psalm 7 functions as a courtroom appeal for divine judgment, and its numeric structure gestures toward the Lord’s Prayer as the daily liturgical key for deliverance from evil, while simultaneously warning against substitute “complete” systems that imitate wholeness but deny Christ.

Keywords

Psalm 7; Lord’s Prayer; Luke 11; deliverance; judgment; biblical mathematics; divisors; sum-of-divisors; typology; discernment; 108; 153

1. Introduction

Psalm 7 is a juridical lament: a prayer shaped like a court case. The psalmist (David, per superscription) pleads for refuge, protests integrity against accusation, summons divine judgment, and ends in praise. The theological center is not vengeance but justice: God judges truly, tests hearts, shields the upright, and causes evil to collapse on itself.

Within the Biblical Mathematics framework developed in this project, Psalm 7 becomes a test case: can numeric invariants illuminate theological contours already present in the text—without replacing exegesis, but serving as a structural “witness” to meaning? The findings below suggest that divisor-structure functions not as arbitrary play, but as an interpretive bridge that intensifies three themes already central to Psalm 7: (i) God as Judge, (ii) evil recoiling on the evildoer, and (iii) prayer as the faithful posture while awaiting God’s verdict.

2. Textual-Theological Context of Psalm 7

Psalm 7 is framed by crisis: persecution, false accusation, and the threat of being “torn” like prey. The psalmist’s protestation (“if I have done this…”) is not a denial of all sinfulness, but a claim of innocence regarding the specific charge at hand. This is covenantal courtroom language: David appeals to God’s righteous governance rather than to self-help, manipulation, or retaliation.

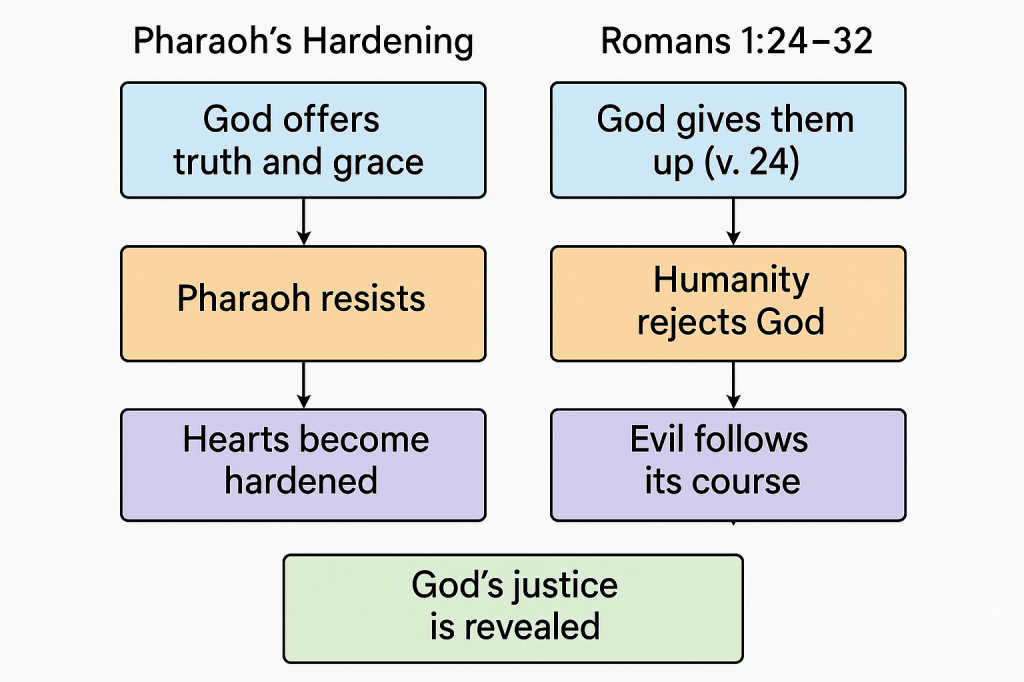

The psalm’s inner logic culminates in the moral boomerang of vv. 14–16: the wicked “conceive” trouble, “dig a pit,” and “fall into” their own snare; violence returns upon their own head. The closing vow of praise asserts that God’s righteousness is not merely feared but celebrated.

From a Christian perspective, Psalm 7 is not a direct predictive messianic oracle in the manner of Psalm 22, yet it readily participates in a typological arc: the righteous sufferer falsely accused, entrusting vindication to God, resonates with the passion of Christ and the New Testament’s insistence that God is the ultimate Judge.

3. Methodology

3.1 Verse Identifier System

We use the Verse Identifier:

For Psalms, Book# = 19 (standard Protestant ordering). For Luke, Book# = 42.

3.2 Canon of Numeric Invariants (Operational Form)

We apply four invariants to a passage total :

- Divisor set

- Number of divisors

- Sum-of-divisors

- Mean divisor value

In this project’s interpretive practice:

- Divisors function as “structural witnesses” (what can enter the number evenly).

- Sum-of-divisors often behaves as a bridge: a fullness measure that can land on a theologically aligned signature.

- Divisor mean functions as a centering signal that may invite discernment (true vs counterfeit completeness).

4. Results

4.1 The “Moral Recoil” Unit (Psalm 7:14–16)

Identifiers (Psalms = Book 19; Chapter 7):

- Psalm 7:14 →

- Psalm 7:15 →

- Psalm 7:16 →

Total:

Divisors:

4.2 Luke’s Lord’s Prayer Block (Luke 11:2–4)

Identifiers (Luke = Book 42; Chapter 11):

- Luke 11:2 →

- Luke 11:3 →

- Luke 11:4 →

Total:

Thus:

4.3 Full Psalm 7 Total and the 108 Mean

From the earlier Psalm 7 identifier table, the cumulative total is:

Prime factorization:

Divisors:

Sum-of-divisors:

Number of divisors:

Mean:

5. Theological Interpretation

5.1 Psalm 7’s Courtroom Theology and the “Bridge” to Luke 11

Psalm 7’s defining move is to relocate conflict into God’s courtroom. The psalmist does not deny danger; he denies ultimate agency to his enemies. He petitions the Judge. This is precisely the posture Jesus teaches in Luke 11: prayer that begins with God’s holiness and kingdom and culminates in daily provision, forgiveness, and deliverance from evil.

The numeric bridge is therefore not a random coincidence in this framework; it maps onto an already coherent theological relation:

- Psalm 7:14–16 describes the mechanism of evil (conception → trap → recoil).

- Luke 11:2–4 provides the daily liturgical response by which disciples ask God to govern life under temptation, debt, and evil.

In short: the psalm’s moral architecture finds its devotional key in the Lord’s Prayer.

5.2 The Specificity of “Deliver us from evil”

Luke’s prayer-form includes the explicit petition “deliver us from evil” (Luke 11:4). The Psalm 7 recoil unit is, functionally, a portrait of deliverance: God does not merely remove the righteous from danger; He overturns the wicked scheme so that violence collapses upon itself. The bridge reads like a mathematical witness that the Lord’s Prayer is not only doctrine but an enacted theology of deliverance—prayed into the very dynamics Psalm 7 describes.

5.3 Completion and Spiritual Perfection: Psalm 7 as a Seventh Psalm

Within the biblical numerology appendix adopted in The Lord’s Prayer: A Mathematician’s Creed, the number 7 is associated with “Completion” and “Spiritual Perfection.” Psalm 7, as the seventh psalm, is structurally poised to present a complete moral-theological cycle: accusation → appeal → judgment → recoil → praise. The “completion” is not merely narrative; it is doxological: the faithful end in worship, not obsession.

5.4 595 and the Mean 108: Centering, Counterfeit Completeness, and Discernment

The divisor mean of the full psalm total, , introduces a second layer of interpretation: discernment.

It is well known that the numeral 108 functions as a “completion-of-devotion” number in several Eastern traditions (e.g., 108 names, 108 beads, 108 ritual repetitions). From an orthodox biblical/Christian viewpoint, devotional systems directed to other gods are understood as idolatrous substitutes—religiously impressive, spiritually comprehensive, but not the redemption God gives.

Thus, 108 can be treated as a symbol of “unified counterfeit” completeness when tied to devotion directed away from the God of Israel, and it is explicitly contrasted with the Lord’s Prayer as a Christ-centered counter-symbol. Also 108 can be framed as a “counterfeit fullness,” set in opposition to Christ’s true completeness, even using the mirror motif (801 ↔ 108) to portray imitation-versus-truth dynamics.

Read this way, Psalm 7’s 108-mean becomes spiritually apt: Psalm 7 is exactly the kind of psalm one prays when tempted to grasp for “complete solutions” in the wrong places—self-justification, revenge, manipulative spiritual techniques, or any totalizing system promising safety apart from covenant trust. The psalm teaches the opposite: the righteous flee to God as Judge and wait for His verdict.

This is where Psalm 7’s two discoveries interact powerfully:

- The bridge to 168 says: the proper response is Christ’s prayer-life—“deliver us from evil.”

- The centering 108 warns: in crisis, counterfeit completeness is attractive; resist devotion divorced from Christ.

So the mathematics does not invent a theology foreign to the text. It intensifies what the psalm already demands: fidelity to the true Judge rather than escape into substitute systems.

5.5 The Lord’s Prayer as Creed and Covenant Practice

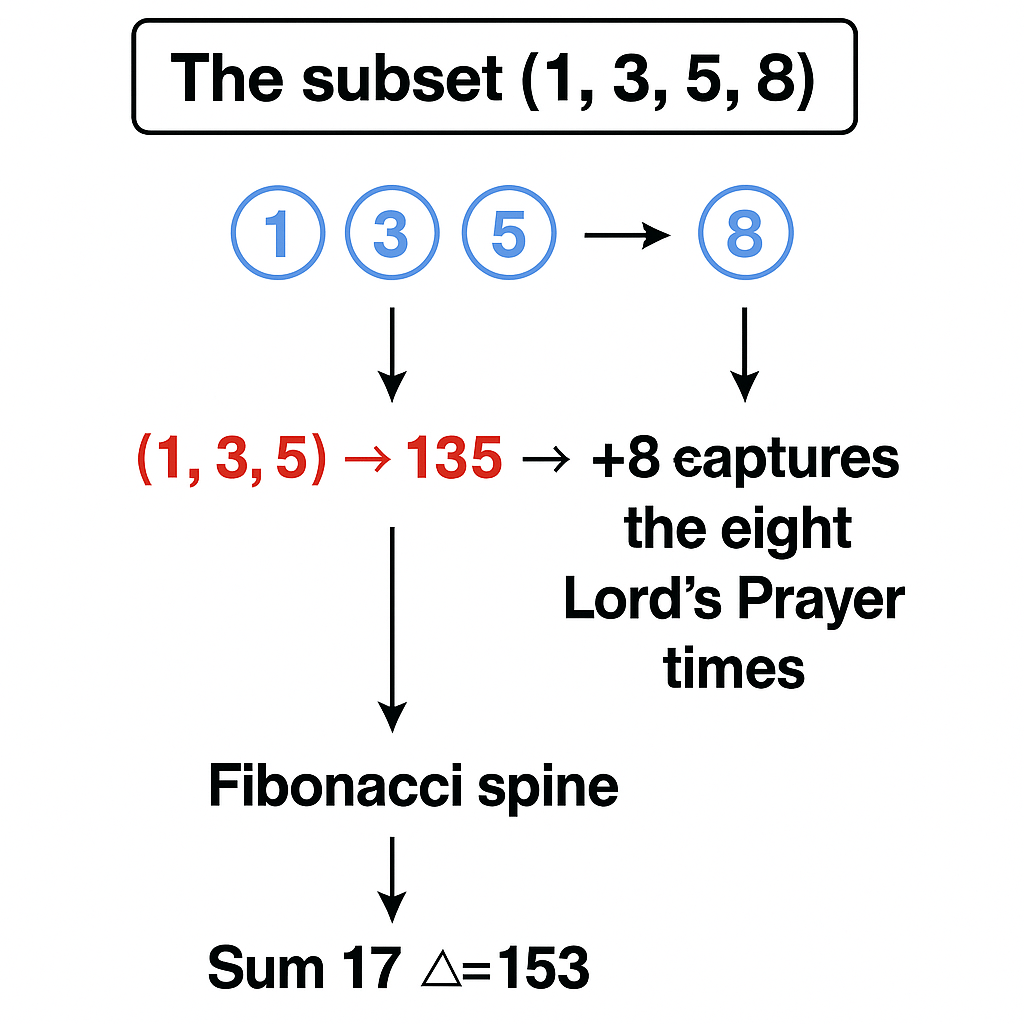

The Lord’s Prayer is not merely a devotional form but a proclamation of faith—indeed “the foremost proclamation of faith,” encompassing Christ’s death, resurrection, ascension, and return to judge, and is linked to the number 153 within our biblical mathematics results.

This matters for Psalm 7 because Psalm 7 is a judgment psalm: God judges peoples, tries hearts, and vindicates the righteous. Our framing of the Lord’s Prayer as creed (and covenant practice) means that praying it is not escapism; it is aligning oneself with the coming judgment and choosing trust over retaliation. Psalm 7’s courtroom is not abandoned in Luke 11; it is carried forward into the disciples’ daily life.

6. A Synthesis: Psalm 7 as a Two-Threshold Psalm

Within the Canon of Numeric Invariants, Psalm 7 can be read as a “two-threshold” structure:

- Threshold of Deliverance (123 → σ → 168):

The moral recoil unit opens into the Lord’s Prayer total, suggesting that the psalm’s teaching about evil’s self-defeat is meant to be prayed—regularly—through Christ’s own words. - Threshold of Discernment (595 → mean → 108):

The psalm’s full architecture centers on a number treated in our apologetic framework as counterfeit completeness, thereby warning that crises often push people toward comprehensive “answers” that are not God. The text itself already insists: only God is Judge and shield.

In theological terms: Psalm 7 teaches both deliverance and discernment—deliverance from evil and discernment against the counterfeit.

7. Implications for Devotion and Formation

- Liturgical implication: The Lord’s Prayer is not merely compatible with Psalm 7; it is a practical “key” for living Psalm 7’s theology daily—especially the petition for deliverance from evil.

- Moral implication: Psalm 7’s recoil logic underwrites a Christian ethic of non-retaliation-with-faith: the righteous entrust judgment to God.

- Discernment implication: The 108-centering invites vigilance: when under accusation or threat, the human heart seeks total solutions; Psalm 7 directs the heart back to covenant trust, and the Lord’s Prayer provides the Christ-given form of that trust.

8. Limitations and Next Steps

This paper works within a defined interpretive framework (Verse Identifiers + Numeric Invariants). The results are internally consistent and theologically coherent with the texts in question, but prudence requires continued testing across other psalms and prayer passages. Next steps could include:

- extending the same invariant analysis to adjacent psalms (3–8) to test whether similar “prayer-bridges” recur;

- mapping recoil/justice units elsewhere in Psalms to New Testament prayer teachings;

- integrating further invariants (aliquot sums, totients) as secondary witnesses, not primary drivers.

9. Conclusion

Psalm 7 is a courtroom lament that culminates in a profound moral truth: evil is self-defeating under God’s righteous rule. Using the Canon of Numeric Invariants, we found (i) a bridge from Psalm 7’s recoil unit (123) to Luke’s Lord’s Prayer block via σ(123)=168, and (ii) a centering signal in the full psalm total whose divisor mean is 108, interpreted in this project as counterfeit completeness when devotion is detached from Christ. Together, these findings cohere into a single theological claim: Psalm 7’s justice and deliverance are meant to be inhabited through Christ’s prayer, while resisting counterfeit systems that mimic completeness. In the life of faith, the psalm trains believers to submit their case to the Judge and to pray their way into deliverance—daily.

References

- The Lord’s Prayer: A Mathematician’s Creed (project text), especially the framing of the Lord’s Prayer as proclamation of faith and its linkage to 153.

- The Biblical Meaning of Numbers from One to Forty (project reference; Appendix reproduced in the Mathematician’s Creed), including the meaning of seven as completion/spiritual perfection.